Two or three years ago, growth for courier companies usually meant increasing square footage, which in turn would lead to higher rent and overheads.

But heading into 2026, things look very different. There are fewer available warehouses than ever and those that are have eye-watering leases. So much so, that the tactic of just opening another depot has become one of the most expensive ways to expand.

Courier companies are having to think more strategically about what they want to achieve with growth. If a new depot doesn’t have a clear tangible benefit (like lower mileage or a more convenient location) it’s not an asset anymore.

This probably leaves you pondering an important question: which models will actually improve my company’s efficiency over the next year?

To get a better idea of what’s working and what’s not, we spoke to Mark Whelan, Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics. His company is one of those turning to collaboration and building smarter networks instead of buying/renting more square footage.

“We’ve increased our daily volumes by 30% while still operating out of one depot,” says Whelan. Instead of opening multiple smaller depots across the region, he has partnered with three other courier companies in various facilities to reach more areas.

Here’s a rundown of the most common depot models and how they’ll fare in 2026.

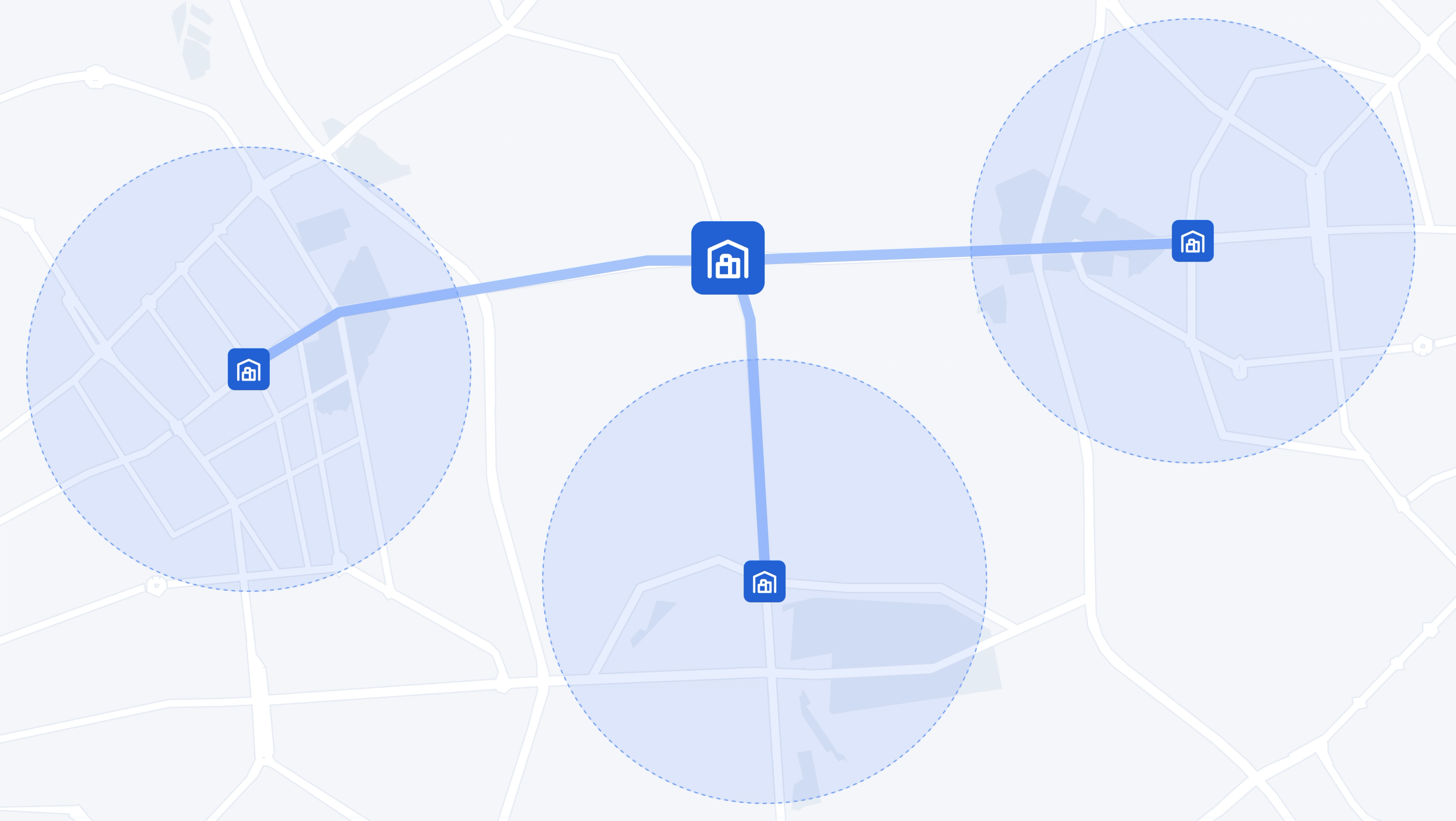

Satellite depots: reliability for rural coverage

Satellite depots are small outpost warehouses that feed local delivery zones.

They're a variation of the traditional hub and spoke logistics model where one central hub is supported by smaller satellite depots for courier networks to reach more locations.

And in 2026, they’ll remain a viable way for companies to grow, especially in situations where geography or real estate doesn’t allow for a single mega-hub .

“Satellites are still a popular option, especially with the way the property market is,” says Whelan, who spent months searching in vain for an affordable new depot.

With “little to no second-hand rental warehouses available”, his company settled for a former courier facility near an airport, which was basically one of the only workable options at the time.

This story echoes a broader trend in the industry: dwindling numbers of industrial properties plus increasingly high rents are making satellite sites an attractive stepping stone when full-service depots are out of reach.

Evidence supports this theory that satellites can improve service but only if they’re stable. Whelan mentioned a DHL satellite in western Ireland that has helped them increase rural deliveries from every-other-day to every day, since vans could leave locally each morning without long backhauls.

“DHL has run a satellite depot in the west of Ireland for ten years. We’ve seen that it’s improved delivery times within the region massively and improved service to rural areas. The knock on effect meant that the main depot at Shannon airport was able to take on more contracts.”

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

This isn’t an anomaly, either. One study found satellites reduced travel distance by 22%.

But the biggest benefit of a satellite depot is that it takes pressure off the main hub. Once the long, awkward rural routes are out the way, the main depot is free to take on fresh contracts.

That said, satellites aren’t really “growth engines” in the traditional sense. Instead, they offer some semblance of stability so couriers can increase their reach without spending huge amounts.

Brad Clements, HR Recruiter and Process Automation Specialist at Falcon Express, recounts a case in Maryland where a satellite that seemed like a great fix collapsed in a matter of months because the volume was so up and down.

"It was only a 1,000 square foot depot, but it worked brilliantly on busy days. On less busy days, not so much. As soon as package counts fell, idle drivers were left twiddling their thumbs while the company still paid out for rent and utilities."

Brad Clements

HR recruiter & process automation specialist at Falcon Express

Yes, satellites work well, until they don’t. If you can’t guarantee consistent volume and struggle to cover the lease during lulls, it may not be the best model.

The 2026 outlook

Satellite depots will still be a popular way for courier companies to expand into regions where a single hub isn’t as efficient. This will mostly be to cover rural areas or secondary cities, or for couriers who need to be closer to spread-out clients.

(We created a guide on how to get more last mile contracts specifically for courier companies. Take a look if you have time.)

Micro-hubs: the pressure valve for main depots

Micro-hubs are small urban sites or space set aside in an existing warehouse that puts freight closer to where it’s going.

Unlike regional satellites, they tend to serve dense city areas so couriers can manage shorter, local runs (sometimes using cargo bikes or EVs).

Whelan is optimistic about micro-hubs and expects them to grow in 2026 as couriers realize they “can save a lot of money by holding their client’s stock in these depots” and relieve the pressure on main centers.

He illustrates how these work in practice using his own experience. His team was getting pallets from UPS and DHL mixed in with their normal parcels, but the pallets were eating up van space they couldn’t really afford to lose. Instead of sending a few bulky pallets out on vans each day, they walled off a small section of the depot and turned it into a micro-hub.

“We decided to shelve off an area of the warehouse, and we can now hold the pallets for up to three days,” says Whelan..

Then, on day four, a third-party truck comes in and collects everything in one go. This is a clever strategy, because batching and consolidating deliveries like this gives the company more space in their daily route.

“We've been able to increase the driver's routes and give them more stops, because they don't need to keep the space for the pallets.”

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

Micro-hubs also play into the growing need for sustainable options. Storing stock closer to dense delivery zones means drivers don’t have to travel as far. And, in some places, you can hand off the last mile to e-bikes that can reach tricky pedestrianized areas.

Micro-hubs could be seen as a major stepping stone toward modern UCC models (we talk more about that further down). At the moment, most micro-hubs are quick and dirty workarounds, but they have the potential to become collaborative nodes if you follow this process:

- You stage your own freight

- You store a partner’s stock

- You start co-loading

- You’re partway to a shared micro-depot network

But Mark warns that it can be a real headache finding the space.

“Our racks are full. It was raining one morning, we had about 10 pallets to come in, you know, I was leaving them along the driveway and along by conveyor belts, and it just, it isn't pretty."

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

Physical capacity can quickly max out, especially if you’re taking stock from multiple clients. Micro-hubs can also delay deliveries for the end customer. If parcels are held back so they can all go out in one run, customers tracking their packages might see it as “out for delivery” but not get it for another day or two.

The 2026 outlook

Micro-hubs will become more common in congested metro areas and places with strong green initiatives. They’re a good way for courier companies to grow sideways before they grow outwards, particularly when space is scarce and property costs are through the roof.

There’s a strong chance we’ll also see more shared micro-hubs or municipalities offering depot space for multiple carriers at once.

Micro-hubs are one way to take the pressure of a depot, but they’re not the only way.

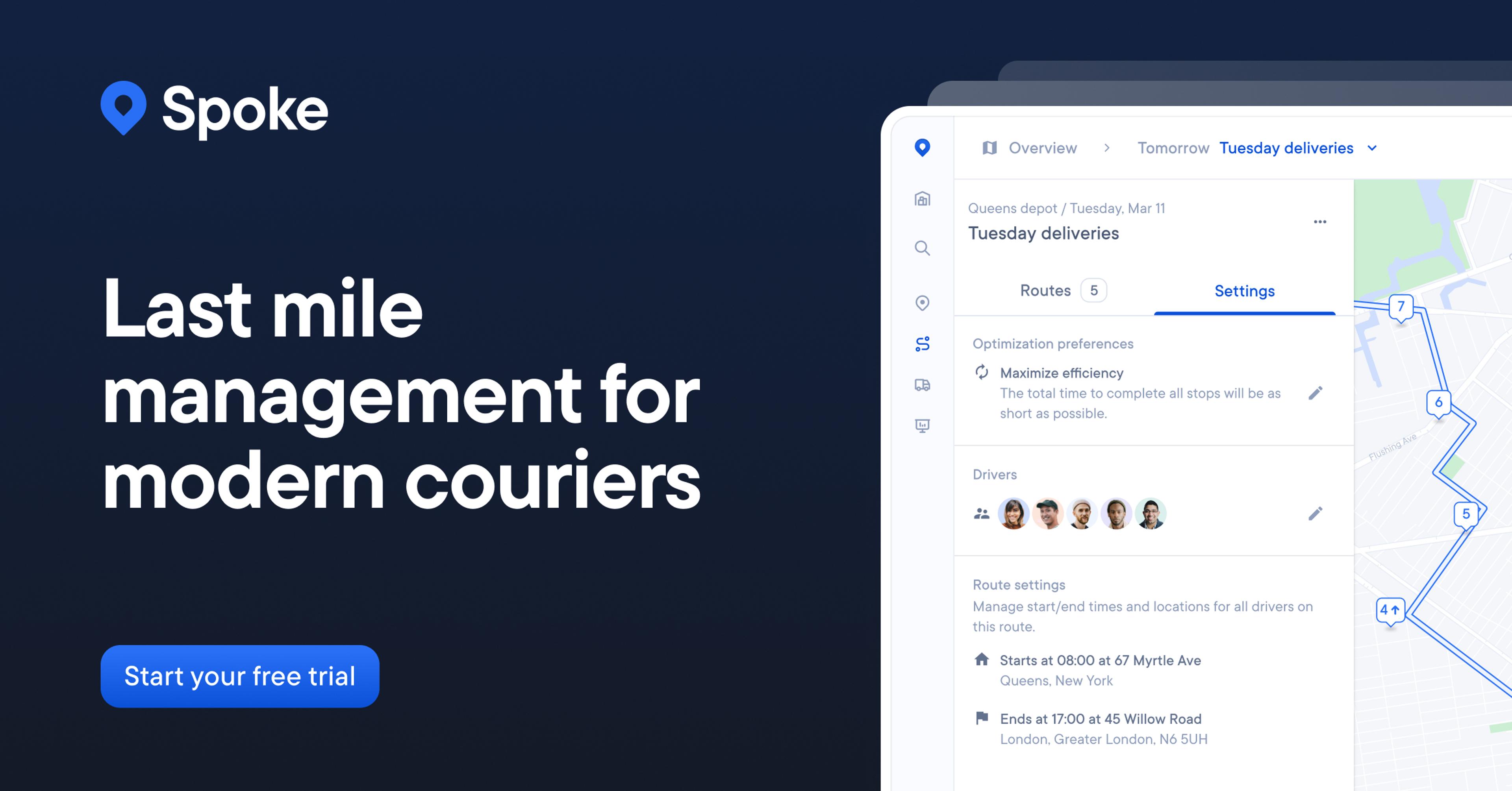

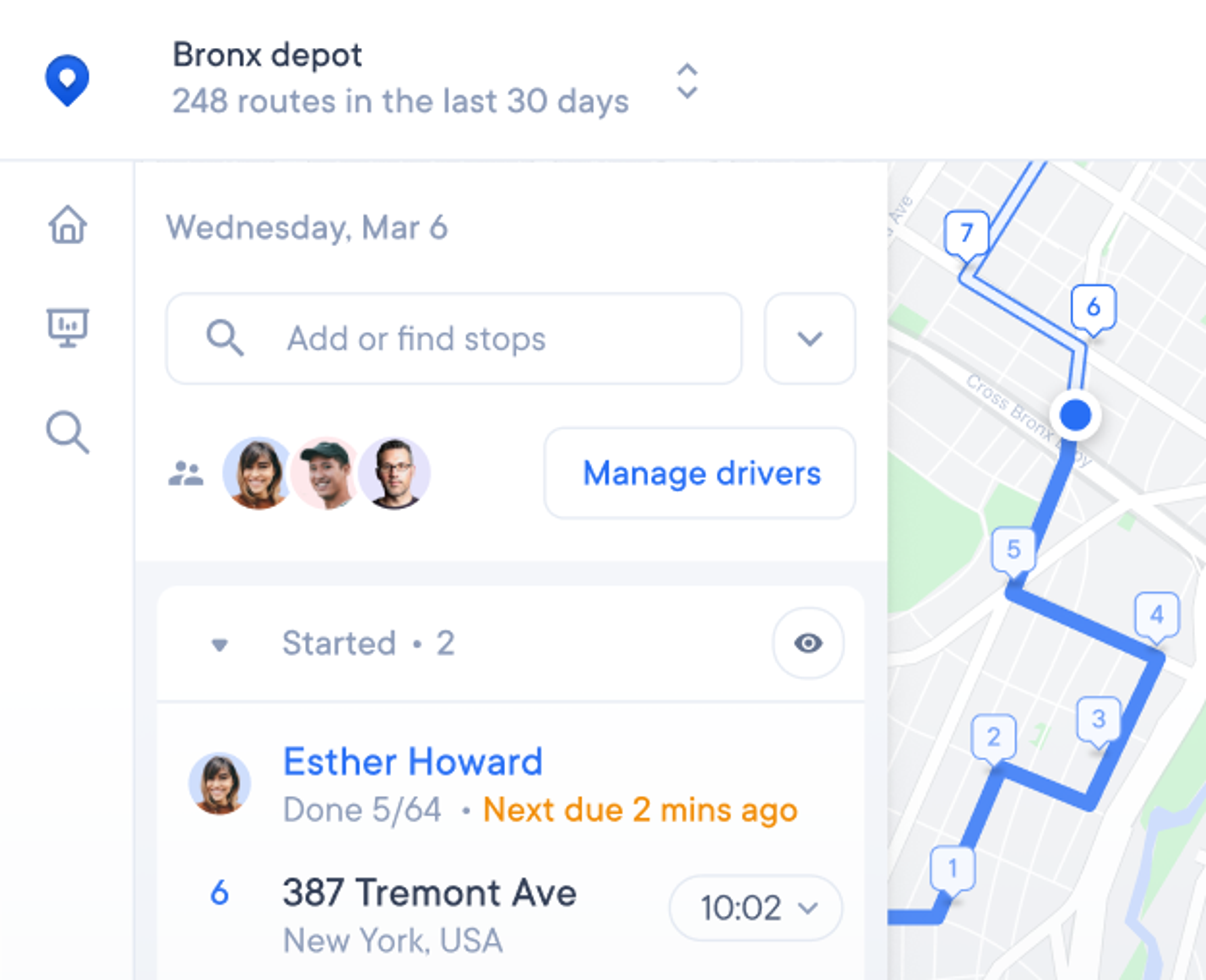

You can actually get a lot of the benefits that come with a new building by just running your network smarter, but you need the right last mile management software.

Having total visibility across drivers, routes and handoffs can make it feel like your existing depot is much bigger than it is (but sans the hefty lease and overheads).

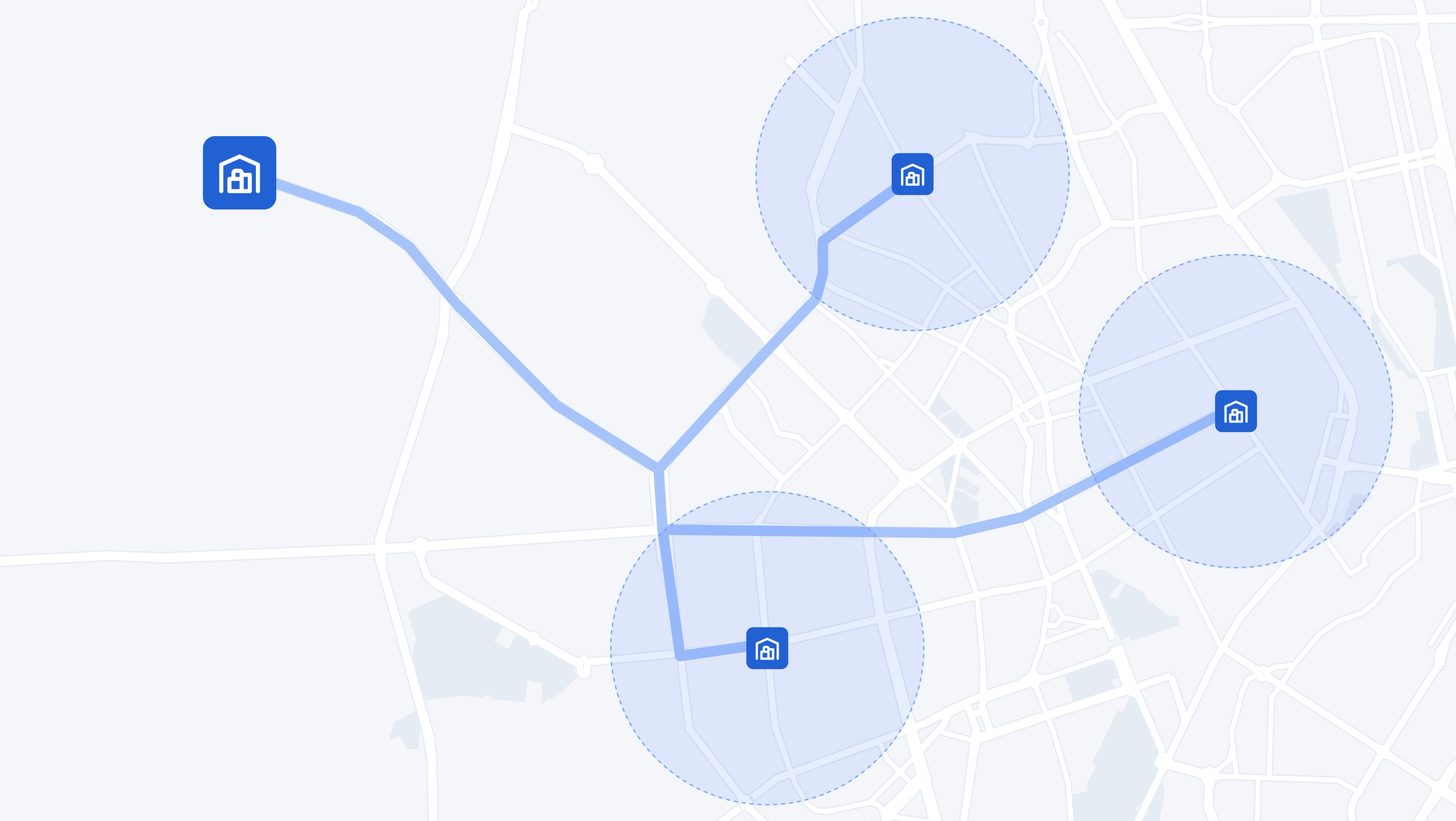

UCC’s and the future of courier growth

We've had quite a few real conversations with courier companies, and many times the consensus is that the future isn't drones, it'd demand aggregation. And perhaps the most hyped (and debated) future depot model is the Urban Consolidation Center (UCC). These are shared depots where multiple courier companies operate from the same place. They co-load freight and pool resources together so each carrier shares the cost. Deliveries are then combined so routes don’t overlap.

Basically, everyone plays happy families, and Whelan is openly optimistic about it all:

“I believe these will be adopted more and more by courier companies. We adopted this model and we’ve been able to grow very successfully, reporting a very comfortable 30% increase in daily volume without having to add any depots to the mix.”

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

Working with other regional couriers means Whelan’s company can operate from one main hub but still cover more territory. “We have three courier companies on board,” he says, all of which co-load from the same depot in western Ireland.

“We took on UPS first, then moved into a shared building with GLS. Now DHL co-loads with GLS,” he adds, claiming it’s been a major success.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. Mark admits the biggest barrier was getting big couriers to permit co-loading. Having DHL parcels rub up against a competitor is not a small ask. But, when DHL saw how much more cost-effective it was to have their rural routes covered this way, they were “quite happy with it."

Traditional model | UCC model |

|---|---|

Three carriers all running separate vans into the same region | One shared run delivers all three |

Duplicate rural routes | Consolidated territory coverage |

Everyone paying separately for space, fleet, admin etc | Shared infrastructure and shared costs |

Drivers half-loaded in remote areas | Vehicles running at proper density |

From duplication to collaboration: can the UCC model really transform regional delivery networks in 2026?

Why UCCs and why now?

From what we’ve seen, there are three core drivers that are making UCCs an undeniably good option for the future.

- Cost and the property landscape. Depots are harder to come by, especially urban ones. Shared sites distribute overheads, which can make a huge difference for mid-sized couriers.

- Increasingly green initiatives. Cities don’t explicitly ask courier companies to co-load, but the only way to lower mileage per package without absolutely crushing margins is to run fuller routes.

- Better technology. Modern UCCs are so workable because there’s better visibility today thanks to improved tech. Scanning, shared ETAs, proof-of-delivery, and depot-level tracking is much easier than before and means all sharing couriers can see the same info.

All sounds good so far, right? Except for one fairly significant problem. Most couriers are taught from day dot that to have a competitive advantage, they need to monopolize territory. And sharing your space or co-loading with competitors completely counters that notion. This is precisely why so many UCC pilots fizzled out. It’s a good idea, but the buy-in is terrible.

Clements can attest to this with a cautionary tale of a UCC pilot in Washington D.C. Initially, it looked great, with low shared costs, drivers in and out in 30 minutes, and the overhead spread across several companies. But as more delivery firms piled in, the operation quickly became a total mess with massive morning logjams. Too many cooks, as the saying goes.

There were a few attempts to negotiate more dock access and stagger schedules, but in the end, the huge delays completely killed the shared line. Clements’ company was one of the first to pull out as on-the-ground bottlenecks outweighed the theoretical savings.

The 2026 outlook

It’s highly likely UCCs will gain traction next year, especially with the crushing state of the commercial property market. In theory, the idea of sharing space with other couriers is a good idea, but the proof will be whether the potential benefits outweigh the ingrained idea that competitors can’t collaborate.

There does seem to be a growing enthusiasm for this model, though, especially when couriers start seeing results. And there’s a good chance there will be more municipal support for UCC pilots, particularly in very green cities.

Cross-docking: too complex in 2026?

Cross-docking isn’t really a depot model (it’s more an operational process), but we’re including it here because it’s still common in certain industries.

Freight comes in the door on one vehicle and goes straight back out on another with little to no storage in between. In theory, it’s great, because there are no warehouse costs and a much faster turnaround. But most couriers are finding that the theory only really holds up in very specific use cases.

Whelan is pretty doubtful about it. He calls it “too time consuming” and labor-intensive for general courier work. Unless a courier’s main depot is severely suboptimal, he says it’s not worth it.

“We prefer to manage our area from a central hub rather than moving stuff into other areas and redistributing it”

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

He uses an example of a competitor in his region who doesn’t have their depot in a central location. They’ve been forced into a nightly cross-dock routine where a truck arrives at 2am, is unloaded, and reloaded onto a smaller vehicle. It works, but it’s twice the handling.

That said, cross-docking can be effective in certain situations. Clements illustrates a case from an overnight frozen meat delivery program for high-end restaurants that purely uses cross-docking.

Every night between 12am and 3am, premium steaks and seafood get loaded onto refrigerated vans for the 7am breakfast deliveries. This means the meat is only in the warehouse for three hours at a time.

The 2026 outlook

Cross-docking certainly won’t be the depot model of the future, but it’ll continue to be a niche tool for industry-specific couriers. It’s still a great option for specialized supply chains in the grocery and pharmaceutical industries, as well as any scenarios that have tight delivery windows.

For general courier companies, though, cross-docking every single package between depots just adds steps to an already complex process.

PUDO networks: growing, but still retail-led

PUDO (pick-up/drop-off) networks include locker banks, convenience stores, and parcel shops where customers can pick up or return packages. They’re not exactly part of a depot network, but they are a key part of depot strategy, particularly now with the Amazon Effect and consumers wanting more control over their deliveries.

The demand for them is coming from ecom buyers and consumers who want a bit more flexibility with their deliveries rather than the courier companies themselves. And this is an interesting point for the future, because many, including us, believe that more recipient control in terms of how they get their delivery is where the last mile industry is going.

Whelan notes a modest but definite climb in the number of customers choosing to use lockers in his region. In fact, couriers like DHL and UPS now regularly offer customers the option to ship to a local locker. About 1% of Whelan’s daily deliveries go to automated lockers and around 5% of collections are left in lockers.

The numbers are small, but they’re still there and driven mostly by three main use cases:

- Remote or rural customers who worry a driver won’t cover their area the day of their delivery.

- People not home during working hours who don’t want companies leaving their stuff on their doorstep.

- Apartments and gated buildings with terrible access for drivers.

Clements says delivering to big residential buildings is brutal. “One bad stop could wreck a whole route,” he adds, which is an issue lockers help tackle.

The 2026 outlook

PUDO networks will stick around and continue to grow in 2026 as ecom purchases rise. Expect to see more locker options in delivery apps and possibly even regional locker networks that are run by groups of carriers or startups.

PUDO networks are a quick fix for the last 50 feet problem rather than a core depot strategy, but they do impact overall depot planning (a driver can deliver 20 packages to one locker bank, which is basically a micro-drop). They tend to be a complementary addition for couriers rather than a core depot strategy.

Pop-up depots: useful, but unsustainable for scale

Pop-up depots are temporary distribution centers set up to absorb demand during peak seasons (usually the busy Q4 shopping season). They’re often in a rented warehouse or lot spaces with trailers, but the main takeaway is that they are only used for a few weeks or months at a time and then they’re shut down.

Whelan claims pop-ups are predominantly used for seasonal spikes because it’s too much hassle to set them up outside of peak times. In fact, many regional operators would consider it too much hassle at any time of the year.

“Our peak season strategy, we hire more drivers, we get more vans, we put on more delivery routes, and we have staggered shifts in the morning. Then our other strategy would be, we'd hold a certain amount of deliveries for future days so we can spread the workload when some days are busier than others.”

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

He believes it’s completely counterproductive to add an entire new physical node that will just be shut down again a month later.

That said, pop-ups can work well in certain scenarios. Whelan does admit that if a pop-up is low-hassle and low-commitment it can be set up and closed quickly if it’s not working or the contract ends.

So, flexibility is a bonus here. This could be an attractive advantage for big ecommerce carriers and 3PLs who might roll out pop-up sorting centers during the holidays to get closer to customers for 8-10 weeks. Pop-ups can also be a good way to pilot a new region without going all in.

Here’s the big but. Whelan claims pop-ups don’t do much for long-term growth. They are, by nature, reactive and transient. You simply can’t build a steady customer base or pool of drivers around a depot that appears then disappears.

The 2026 outlook

Pop-up depots will primarily be used for peak seasons or one-off projects. They’re not “growing” in the sense that they’re being widely adopted by all courier companies all throughout the year. We might see slightly more sophisticated uses of pop-ups, like pre-packaged “warehouse-in-a-box” solutions, but for the most part, pop-ups will stay niche and season-specific.

Choosing the right depot model: lessons from 2025

If there’s one thing that rings true throughout all of this, it’s that your choice of depot model isn’t as important as your location. A badly positioned depot with a good model won’t function anywhere near as well as a well-positioned depot with the same model.

Mark summed this up perfectly.

“I think depot location is one to look at, and it was certainly one that when we made the move. We didn't actually think that staying in one location could hold you back”.

Mark Whelan

Operations & Systems Manager at Express Logistics

Express Logistic’s location right by the airport means drivers only have to travel one hour to get anywhere in the region.

The other thing to consider is that many of these concepts look ideal on paper, but the cracks start to show in practice. Sometimes it’s just as simple as the best depot model is the one that lets you be flexible and cover more places from a single, well-located site.

Some things to think about before you dive in:

- Can you afford the extra lease and staff even in off-peak months?

- Do you have enough work to justify the model for the whole year?

- Will you have reliable access to the infrastructure you need every day?

And here’s a quick recap of the different depot models and their outlook for 2026.

Model | 2026 trajectory | Best use case |

|---|---|---|

UCCs | Rising | Where multiple carriers have overlapping routes or rural coverage isn’t worth it alone |

Micro-hubs | Rising | To relieve pressure in dense urban areas and increase sustainability in green zones |

Satellites | Stable | Expand into regions the core depot struggles to reach easily |

PUDO | Slow, steady growth | Good customer experience and reducing the number of failed deliveries |

Cross-docking | Niche | Specialized supply chains like perishables and pharma |

Pop-ups | Niche | Good for peak seasons or relief for short-term spillover |

The 2026 outlook: depot models and their best use cases

Think about approaching any new depot model with a realistic lens (and maybe even a critical one, too). There are ways you can experiment that won’t impact your bottom line too much if they don’t work out. For example, you can run tests in controlled situations, get your drivers to give you honest feedback, and use last mile management technology to get a clear view of what’s happening across your network at all times.

But the main lesson from 2025 is that you don’t have to pick one model and marry it. You can stay fluid with your choices and pick the model that fits your footprint at that exact moment in time and then adapt it when things start to change.

The easiest way to figure out which model actually works for you is to get complete visibility as quickly as possible. The more route and delivery data you have, the easier it is to see whether a satellite, micro-hub, or UCC is pulling its weight (or, you know, draining you completely).

But… you need the right software to do this. When everyone’s working off the same live data, you can test ideas without signing a lease.

If you want to pressure-test your network without building more of it, you can try Spoke Dispatch free for 7 days and see for yourself how it works.

The competitive edge now comes from working together

The truth is, no one really knows for sure what will happen over the next year. What we do know is that the old growth playbook of buying more square footage and monopolizing regions is losing ground to something a bit more collaborative.

The depot models that we’ll see more of in 2026 hinge on strategic partnerships and working together, with an added dose of only building when you absolutely must.

UCCs work because they spread the load, micro-hubs work because they support the main depot without adding extra overheads, and satellites work because they protect the primary center. Even lockers work because they tackle pain points instead of adding new infrastructure.

And it sounds counterproductive to an industry that’s been told to monopolize territory, but it’s going to become increasingly important to start optimizing things from the network level rather than the building level. So, it might feel like a major compromise to co-load or share space with your biggest rivals, but done right, it can actually become a competitive edge.